From: Tubob: Two Years in West Africa with the Peace Corps

One day while living and working in the west African country of The Gambia with the Peace Corps, my husband Bruce and I looked to the east and saw a solid wall of sand coming our way. Fierce winds carried sand and dust with amazing force. The wind was so great, Bruce hung onto a corner of our roof, afraid that it would blow off. I hung on to Bruce. We closed our eyes to the stinging wind and bowed our heads to shield our eyes. When it was over we found sand everywhere, in every crevice, nook and corner.

A harmattan? We’d heard of the harmattan, a strong wind that blows from the Sahara Desert during the dry season. This must have been it.

A couple of weeks later we received a note from George Scharffenburger, The Gambia’s Peace Corps Director. He was bringing his guest, Terry, who was in charge of The Gambia desk at Peace Corps headquarters in Washington, D.C. to visit us. Terry was interested in seeing how Peace Corps volunteers lived and worked in their host country.

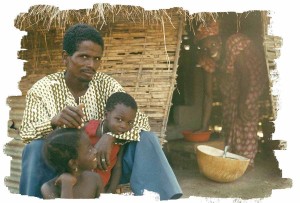

We lived in what was known as the “U.N. compound.” Our living conditions were quite adequate, considering some Peace Corps accommodations. And compared to our African neighbors, our kitchen was luxurious. In The Gambia, most villagers where we lived “up river” in the village of Mansajang, cooked on an open fire, with a large pot balanced on three rocks.

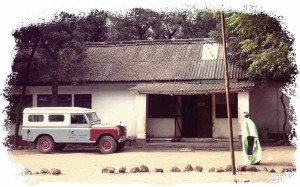

We considered our living situation very special with a 3-room mud-brick 30 x 10-foot house, and a round thatched-roof one-room mud-brick hut, about 20 feet in diameter, that we used for a bedroom. The 3-room house contained a kitchen, a small sitting room where we ate, and a small bedroom. The bedroom was for the convenience of U.N. visiting guests, such as the Frenchman responsible for keeping the many fresh-water well foot-pumps in repair. Bruce worked as a Peace Corps volunteer for the United Nations well-digging unit, while I was a health worker based at the Basse Health Centre.

By American standards, our 3-room house was very crude. There was no glass in the windows, nor screens. There was a large gap between the corrugated roof and walls, and all that openness meant flying insects had easy entry. The kitchen didn’t have running water; in fact, it didn’t have a sink. We did have a small refrigerator, which was a blessing, and a small propane 3-burner stove, much like a camp stove. There were no enclosed built-in cupboards, but we fashioned a set of shelves for our food supplies. Our pots and pans, dishes and silverware were arranged on a table, which also served as my work space to prepare meals.

Our shared latrine, merely a hole in the ground, was in a corner of the compound with a thatched fence around it for privacy.

An African family also lived in the compound, plus there were two empty huts, placed there for the convenience of traveling U.N. drivers transporting supplies back and forth 250 miles to the capital city, Banjul. The African family of 4 lived in a round hut exactly like the one we used as our bedroom.

George and Terry arrived bearing mail for us from our family. There was no individual mail service where we lived, but it was the custom for people coming from the capital city to bring mail with them. We showed them around; Terry was obviously impressed and mentioned that we had a nice arrangement. Up-river where we lived in “the bush” was noticeably hotter than down-river where they had the benefit of ocean breezes.

Terry soon wanted to take a shower. She was a bit taken aback, when I showed her our “shower,” which amounted to a wooden platform with two full buckets of water. Terry had never taken a bucket bath, but she was game. Actually, I think she thought it quaint. When finished, I noticed she didn’t go to the well to refill the buckets for the next person, as she had found them. The well we used served the entire village of Mansajang.

I served dinner, we had a nice visit, then turned in for the night. The “guest” bedroom had two single cots. During the night we had another harmattan. There’s really nothing we could do to protect ourselves or our guests. With all the openings in the small house and nothing but screens in the hut, we just hunkered down to wait it out. This was Terry’s first experience with a harmattan. The next morning she woke up covered with fine sand in her hair, her ears, her bedding, even in her opened suitcase. With resignation, I began washing all the pots, pans, dishes and silverware which lay exposed on the table so that I could begin to prepare our breakfast. But first, I had to dump water out of the kitchen pail, since it was filthy with sand and dirt, and fetch fresh water from the well. Things move slowly in Africa.

Terry obviously no longer felt our living situation quaint. I don’t know that she saw the humor in my statement, “Now you know how a sugar cookie feels.” George and Terry’s enthusiasm for our living conditions vanished. They couldn’t leave fast enough. For us it was business as usual.