Before the Wind by Jim Lynch is a captivating, often hilarious novel about a sailing family, the Johannssens.

The story is narrated by the most seemingly normal member of the family, Josh, now thirty-one, who is the middle of three siblings. Josh’s father is a fanatical sailor and expects the family to live and breathe sailing. Growing up, the family’s every spare moment was spent practicing sailing maneuvers, always with the goal of winning races, especially the famous northwest Swiftsure. Josh’s father and grandfather build and design highly desired boats, though their business is currently on the brink of disaster. Josh’s brilliant though eccentric mother is deep into solving mathematical theories. Bernard, Josh’s older brother has his own version of what he’d like his life to be, and his plan doesn’t necessarily include the family. The youngest child, Ruby, is a sailing genius, but she too, must find her own way.

When the family reunites for one last Swiftsure race, they learn surprising things about one another, truths that will bind them forever.

I loved Before the Wind. Since I have sailed in both Puget Sound and the Pacific, I could appreciate much of the nautical jargon, though the author describes the art of sailing and maintaining a boat with far more intricacy than I will ever know. I especially loved the family dynamics, and the author’s humor in describing life in a marina. Sailors will love this book, but you don’t have to be nautical to appreciate the author’s skill in telling a good story.

Mary E. Trimble

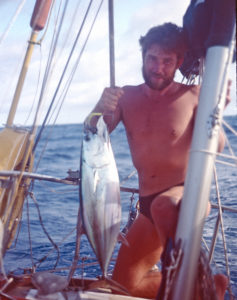

Author: SAILING WITH IMPUNITY