Well, it’s about time. What I had fantasized about for so many years–writing about our two years in West Africa–has at last become a reality. What took me so long? I wonder that myself. I guess in my mind it was such an overwhelming experience, so personal and heart-felt, I wasn’t sure I could put it adequately into words.

For me, it’s easy to make up a story. I’ve done it since I was a little kid. My older sister taught me. I’d beg her to tell me a story and she finally said, “Mary, make up your own story. Think of something you’d like to hear or read, and tell yourself a story.” That first time, she gave me an opening sentence and I took off from there.

Along the way my need to tell stories became three novels, all contemporary western, all well received: Tenderfoot, McClellan’s Bluff, and Rosemount.

But to tell something that’s true, that represents our own heart-felt and hard-won experiences, is different. For some reason I couldn’t get past the idea that it wasn’t a “story,” it was true to life, sometimes painfully so.

Sure, I could write little snippets and I did write about a few experiences on my blog with favorable results and encouragement to write a book. But these were usually positive experiences, and our two years in Africa were not all positive. They were often grueling, discouraging, even scary. But are we glad we did it? Absolutely!

Finally, I decided I would have no peace until I at least tried to write the story about our Peace Corps experience in The Gambia. We had asked our families to save our letters to them. I couldn’t stand the duplication of effort to keep a journal and write home. This was before email, so all our letters were either hand written or typed (I had sacrificed space and weight to take a manual typewriter).

I sorted through all the letters written by both of us, putting them in date order. I began to see I needed to have some sort of index so that I could avoid volumes of data entry, so I created a computer index with various subjects: names, Bruce’s work, my work, animals, etc., and referred to a coded recipient and the date. Soon, I had 42 pages of categorized key words. And I had my inspiration. I relived those years, remembered the sweat and tears, and the joys. Despite the elapsed years, thanks to our letters home, I could recount details that would make the story real to readers.

It took me two months to go through and annotate all the stacks of letters. In January, 2012, I began to write my memoir and wrote straight through to May. Editing and proofing is another matter, but I enjoyed that part, too.

I had worried that I might offend some people we knew in Africa. In most instances, I use actual names for real people. But in a few cases, I have changed the names to avoid hurt feelings or embarrassment. In a couple of instances, in the interest of clarity, I have combined characters.

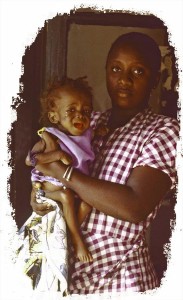

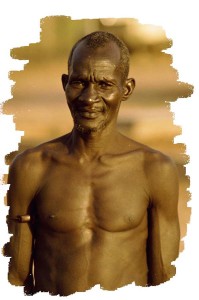

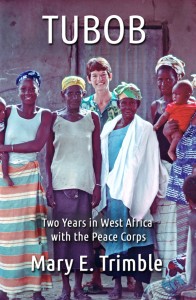

Bruce took hundreds of 35 mm pictures while in The Gambia. We had mounted the slides in trays and every once in awhile we viewed them or shared the pictures and stories with others. Once I could see an actual memoir in the making, we invested in the equipment necessary to convert the slides into digital form. Bruce spent countless hours selecting and editing the pictures so that we would have meaningful images for the beginning of each chapter. Bruce also designed the book’s cover, using his artistic talent to make a cover representative of the story.

So, finally, we have produced an honest recounting of our two years in The Gambia with the Peace Corps. I have made every effort to be objective, and to fairly and honestly tell the story of our time in a third-world country.

Perhaps I needed to wait 30 years so that I could be more objective. Surely, I have gained in wisdom and global awareness in that time. We have never been back to The Gambia, but I hear from people who have and they report not much has changed. Electricity does not reach many homes, people still haul water from a well, many of the struggles remain the same. Education is more available. With the Internet, Peace Corps volunteers now have better communication with family and friends back home. That would be a huge improvement and eliminate many of the anxieties we felt.

Some lessons I learned remain. You take the bad with the good. You live in the moment. And in the bad times, remember that “this too shall pass.”

TUBOB: Two Years in West Africa with the Peace Corps is available at local bookstores, Amazon.com, or through my website, www.MaryTrimbleBooks.com