Note: The following is taken in part from my memoir, Sailing with Impunity: Adventure in the South Pacific.

Early on, we established a four-hours on, four-hours off watch system while at sea. For safety, someone needs to be on deck at all times. Weather can change in a heartbeat, or another vessel could be on a collision course with your boat.

Early on, we established a four-hours on, four-hours off watch system while at sea. For safety, someone needs to be on deck at all times. Weather can change in a heartbeat, or another vessel could be on a collision course with your boat.

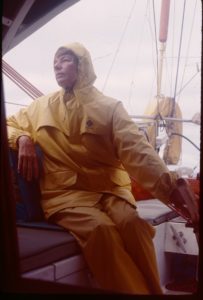

Although our watch system dictated four hours on, four hours off, sometimes we didn’t even get four hours of sleep. We had a safety rule that if one of us went to the forward deck, the other had to be at least in the cockpit. Although when going to the foredeck we always wore our safety harnesses (well, maybe not in dead calm), there was still a danger of losing our balance and falling off the boat. If that should happen, even tethered to a line, the person in the water could be dragged along and unable to get back onto the boat.

Bruce always tried to have Impunity’s sails set conservatively for the night, but there were times he had to wake me during his night watch so that I could be in the cockpit while he changed a jib or took a reef in the mainsail. The sea doesn’t care what your sleeping schedule is.

One night after a particularly calm, peaceful day, I was sleeping when around three in the morning I not only heard, but felt a loud BANG! It sounded as though we’d hit something. I heard Bruce yell, “Mary! I need you on deck!”

I scrambled out of the midship berth and up to the deck into screaming wind and driving rain. Bruce handed me my safety line and I clipped it on as he made his way to the bow, fighting against a strong wind. He took down the jib and lashed it to the railing with a bungee cord, then made his way back to take a couple of reefs in the mainsail, reducing the effect of wind and calming the boat’s action..

Sudden squalls come without warning and can knock a boat down. Since it was dark, Bruce couldn’t see it coming, but he said moments before the squall was on us that he had noticed a subtle wind shift and felt the temperature drop a few degrees. Then, the wind suddenly picked up and the squall slammed into us. Another reason why a person should always be on deck. Without quick action, we could have been in trouble.

On another occasion, while I stood my 10:00 p.m. to 2:00 a.m. watch, I spotted lights from a large ship on the horizon. Although we were the privileged vessel, because of our position relative to the ship and because we were under sail, I kept my eye on the ship. I took bearings repeatedly and after a period of time could see that we were on a collision course.

I hated to wake Bruce, but it was our rule. In situations like this, he never grumbled about being awakened. We monitored the approaching ship together, and it appeared as though they didn’t see us, even though we’d shown our deck lights. The ship made no attempt to change course.

Bruce called on the VHF radio. “To eastbound ship on my port bow, this is the sailing vessel Impunity. Over.” Nothing.

A few minutes later Bruce called again. “To east-bound ship on my port bow, this is the sailing vessel Impunity. Please state your intentions. Over.” No answer.

A third call and still no response.

Because we were the privileged vessel, we were obligated to maintain course and speed. But finally, when we could see that the ship was not going to change course, we had to alter our course in order to avoid a collision. We tacked and went around and behind the ship.

After the collision danger was past and we were back on course, Impunity received a call on the VHF. The caller spoke in a heavily accented voice. He identified his ship as a Japanese freighter heading for the Panama Canal. The captain, possibly the only English-speaking person on board, was apparently asleep when we first called on the radio. Afterward, Bruce, relieved, joked to me, “I thought they were going to make sushi out of us.” In truth, they could easily have hit us, and it is entirely possible that they would not even have known it. They apparently were keeping neither a visual, nor radar, nor radio watch. To them we might have been merely a bump in the night.

As Bruce often joked, “right-of-way is a matter of tonnage.”