The anniversary of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer’s wedding forty years ago, July 29, 1981, conjures up memories of splendor for many people, but for Bruce and me it brings back scary memories.

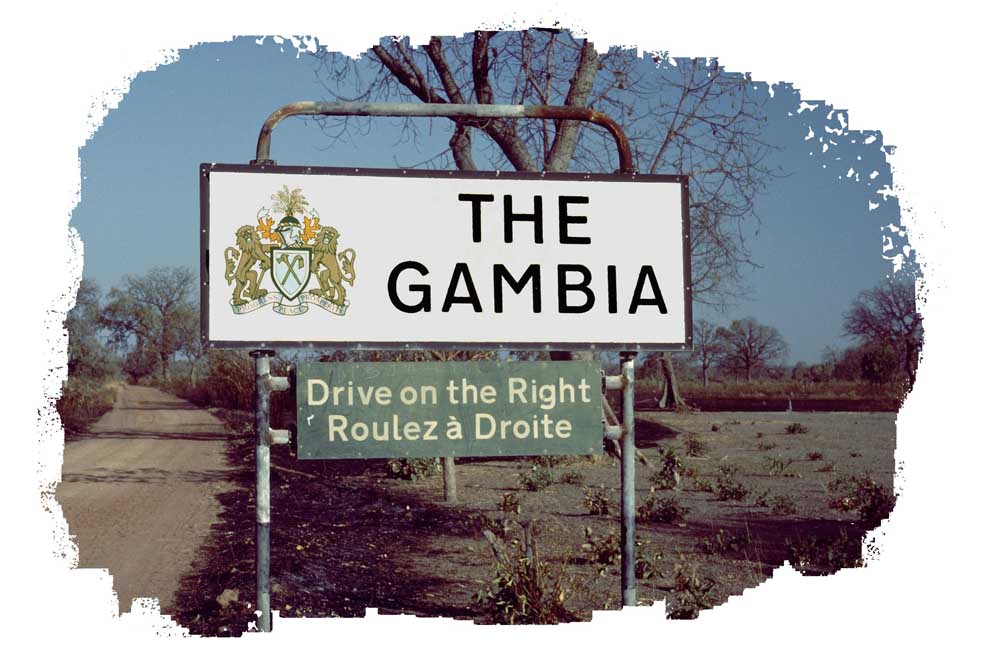

While serving with the Peace Corps in the tiny West African country of The Gambia, we happened to be in the capital city of Banjul, 250 long miles from our “home” village in Mansajang. We had been called to the country’s Peace Corps headquarters for our exit physicals, since we were nearing the end of our two-year tour of duty and were scheduled to leave in September.

We had taken care of our business and were ready to return to Mansajang. We were traveling light since we’d only planned to be in Banjul two or three days. Much to our consternation, we couldn’t get out of Banjul—the entire city was locked down. Main intersections were blocked with tanks and military personnel carriers. Turning on the radio, we were chilled to hear frantic announcements that a military coup had effectively closed down the capitol city, the airport, and much of the country.

While the president of The Gambia, Sir Dawda Jawara, was in England to attend the royal wedding, rebels took advantage of his absence to stage a coup.

After some scurrying around, we ended up at the U.S. Ambassador’s residence. Though nice it wasn’t the grand residence usually associated with a high-ranking officer’s home. At 4,000 square feet, the concrete house wasn’t particularly large—certainly not for the 118 people seeking refuge: Americans, Germans, Swedes, Canadians, Indians, and a few tourists.

Bruce’s skills as a licensed radio operator proved to be a valuable asset. He manned both short-range and a medium-range radios, allowing communication between embassies and to the State Department in the United States.

It was a harrowing eight days of mortars thundering close-by, making the house shudder, flurries of rapid gunfire, yelling, screaming. We ran dangerously short of food, couldn’t take showers because of a diminishing water supply, the electricity was spotty, and nerves were frayed with the crowded conditions. Later we learned that more than 500 people were killed in the fray.

Amazingly, it was British Special Air Service that came to the rescue. A helicopter landed on the beach near the Ambassador’s residence and two SAS (Special Air Service) men, dressed in civilian clothes and armed with MP5s and Browning 9mm pistols, plus hand grenades, called on us, used the radio, and warned us that there soon would be heavy combat noise and to stay inside, assuring us the coup would soon end. The two men had flown in with Senegalese Forces, some of whom surrounded the residence for our protection. Within a very short time, the coup was over.

The Peace Corps people were flown to Senegal for two weeks while the country settled down. We were then free to go back to our villages. I couldn’t wait to tell my Gambian friends where we had been. But they already knew—they’d heard all about it on the drums. The talking drums, now there’s a mystery. But that’s another story.

Note: Read more about this and other stories in my memoir, TUBOB: Two Years in West Africa with the Peace Corps.

It’s great to read/write about this now but I know this must have been frightening at the time. I was in Kano, Nigeria, with the British Council when there was coup. We weren’t as near to the action as you seem to have been, but huddling around the radio for information, unable to lave the compound, and without water was bad enough. I guess we can look back on those times, Mary, as one of life’s great adventures and be thankful we got home.

So interesting, Andrea. I didn’t know you spent time in Africa. The thing is, when you’re in a different country, your “rights” aren’t like they are at home. Also in a coup, even the local people aren’t the same–their loyalties shift.