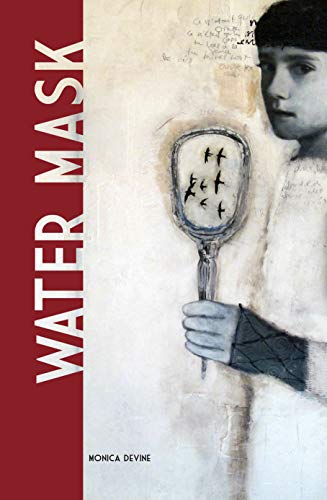

Water Mask by Monica Devine is an impressive collection of fifteen powerful essays about creating a life in the far north. But more than that, it’s a book about being an active participant in your own life, savoring all its parts, and engaging with all that’s around you.

Originally from Michigan, Monica Devine graduated from college with a master’s degree in speech and language pathology. For the next 25 years she worked with Indian and Eskimo children in villages throughout Alaska. During that time, she immersed herself into the land and its people, learning how to not only survive, but to embrace all of life. Living in harsh conditions takes courage and patience. Waiting for weather to clear enough to fly to a distant village may take days, but it’s vital to put faith in a bush pilot’s expertise. Riding a sled over ice can be dangerous, but native whalers know the sound and feel of their frigid world and it’s wise to trust their instincts.

Water Mask primarily centers around rugged Alaska and its challenges of physical and emotional survival, with brief forays to New Mexico, Wyoming and Michigan. The author met and married her husband in Alaska and together they’ve raised a family in the spirit of listening to the land, following its dictates, and embracing all that life has to offer.

Water Mask is a spiritual book in the sense of being one with nature, valuing traditions, recognizing the strength and challenges of nature, and appreciating the wisdom of its native peoples. Don’t rush through this collection of dynamic essays. Each has a message, a theme. Savor the poetry of the author’s words, take seriously the wisdom of cherishing the moment, and learn what it means to adapt to life’s changing conditions.