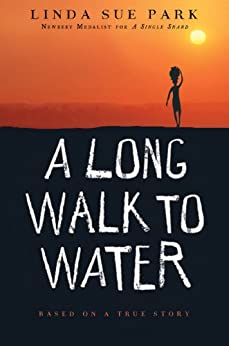

A Long Walk to Water by Linda Sue Park is based on the true 1985 flight of a Sudanese boy, Salva, 11. Each chapter starts with a fictional but realistic section about a young girl, Nya, in southern Sudan beginning in 2008. Nya must make two very long walks daily to fetch water for her family. In reading this poignant account, I imagined that the two stories would intersect, and they eventually do in a surprising and satisfying way.

Salva was at school when the Second Sudanese Civil War finally reached his village. The war began two years earlier between the Muslim-dominated government in the north and the non-Muslim coalition in the south. As marauders approached his school, the teacher told the students to run and to keep going. Salva couldn’t return to his village or to his family because that was where the conflict was taking place. He quickly became separated from the other school children, but eventually found other people to travel with, though they were strangers.

Years passed while Salva walked through Sudan and eventually to Ethiopia going from one refugee camp to another, eventually making his way to a camp in Kenya. By this time he was one of what are now known as “The Lost Boys.” He had been away from his village for eleven years, years of grueling travel or of barely surviving crowded refugee camps.

Nya’s continuing story struck a familiar note for me. Having spent two years in West Africa with the Peace Corps in the small country of The Gambia, I know the value and sometimes scarcity of clean water. Daily I saw young girls come to a fresh-water well close to where we lived, fill huge tubs of water, heft the heavy loads onto their heads, and then walk back to some distant village.

How Nya and Salva’s stories eventually come together is heart warming and shows the price so many in Africa have paid pursuing basic human needs. Salva’s true story is daunting, yet inspiring. Unfortunately, Nya’s story is typical in much of Africa. I recommend A Long Walk to Water for people from ages 9 to 99.